Q&A

From the July AD 2008

Our Lady of the Rosary

Parish BulletinON THIS PAGE:

On “the Just Price?”

On “the Just Price?”Question: Doesn’t the Church have a moral teaching on fair prices? Why don’t we hear anything from the pulpit about the way we are being gouged at the gas pump and the grocery store?

Answer: Saint Thomas Aquinas has a section of the Summa Theologica titled “On cheating, which is committed in buying and selling.”[1] The first article asks “whether it is lawful to sell an article for more than it is worth?” Saint Thomas begins by excluding fraud from any lawful contract. Then he distinguishes two types of buying and selling:

First, as considered in themselves .. buying and selling seem to be established for the common advantage of both parties, one of whom requires that which belongs to the other, and vice versa.... Now whatever is established for the common advantage, should not be more of a burden to one party than to another, and consequently all contracts between them should observe equality of thing and thing. Again, the quality of a thing that comes into human use is measured by the price given for it, for which purpose money was invented.... Therefore if either the price exceed the quantity of the thing's worth, or, conversely, the thing exceed the price, there is no longer the equality of justice: and consequently, to sell a thing for more than its worth, or to buy it for less than its worth, is in itself unjust and unlawful.

Secondly we may speak of buying and selling, considered as accidentally tending to the advantage of one party, and to the disadvantage of the other: for instance, when a man has great need of a certain thing, while an other man will suffer if he be without it. On such a case the just price will depend not only on the thing sold, but on the loss which the sale brings on the seller.....

On the other hand if a man find that he derives great advantage from something he has bought, he may, of his own accord, pay the seller something over and above: and this pertains to his honesty.

Saint Thomas’ fourth article questions “whether it is lawful to sell a thing at a higher price than was paid for it?:

Augustine ... says: “The greedy tradesman blasphemes over his losses; he lies and perjures himself over the price of his wares. But these are vices of the man, not of the craft, which can be exercised without these vices." Therefore trading is not in itself unlawful.”

... The other kind of exchange is either that of money for money, or of any commodity for money, not on account of the necessities of life, but for profit, and this kind of exchange ... regards tradesmen.... [This] latter is justly deserving of blame, because ... it satisfies the greed for gain, which knows no limit and tends to infinity. Hence trading, considered in itself, has a certain debasement attaching thereto, in so far as, by its very nature, it does not imply a virtuous or necessary end. Nevertheless gain which is the end of trading, though not implying, by its nature, anything virtuous or necessary, does not, in itself, connote anything sinful or contrary to virtue: wherefore nothing prevents gain from being directed to some necessary or even virtuous end, and thus trading becomes lawful. Thus, for instance, a man may intend the moderate gain which he seeks to acquire by trading for the upkeep of his household, or for the assistance of the needy: or again, a man may take to trade for some public advantage, for instance, lest his country lack the necessaries of life, and seek gain, not as an end, but as payment for his labor.

So, we see that Saint Thomas speaks both to the notion of a just price, and to lawfulness of being in business to make reasonable profits. Unfortunately, he does not speak to how the just price is determined. But, over the centuries there have been several major theories as to what constitutes the just price of an item.

● The first, held today mostly by Marxists, is that the just price of an item depends on the amount of human labor that was put into its manufacture. Presumably, this includes the labor to provide the raw materials, and perhaps the labor expended to provide things like electricity or water used in the manufacture. If a man takes a day to make an item, he is entitled to a days pay for it. This definition of just price fails an several counts:

What is a day’s pay? Who determines whether he lives at the subsistence level or in luxury? Are his wife and children to be supported at this same level? How many children? Is all labor equal in value? Does physically exhausting labor count for more than light labor? Do working conditions count? Does some level of skill get factored in? Education? What about the worker who brings his own tools, or does not? What about the owner of the building or that land? What about the organizers of the business?

If the just price is determined by solely the difficulty of labor expended, that suggests a very high price for gravel cracked by hand from huge boulders-particularly if it is done in the heat, the rain, and the sun-particularly if it is done down-wind from the sewage treatment plant. Conversely, by this theory, a bolt of fine cloth expertly woven in four hours should cost half as much as a bolt of shoddy woven in eight hours by a competitor.

But how do you compel anyone to buy the high priced pebbles or the bolt of shoddy material? A just price is of little significance it there are no buyers. It is meaningless to say that the gravel justly sells for $100 per pound if no one needs gravel, or if these needing it can buy it from those who just dig nice smooth pebbles out of the creek and whose labor equates to only $25 per pound.

This “labor theory of value” ignores the value inherent in the labor of those with special skills or talents-say, the physician, the computer programmer, the artist or the musician. It generally ignores the owners of the land, buildings, tools, and machinery used in the manufacture. It fails to recognize that things like skyscrapers, suspension bridges, and symphony orchestras do not come into existence without people who organize, and who may do so with very little of what we usually refer to as “labor.”

● If we go back to Saint Thomas’ time we find a few other methods of fixing a “just price.” One of them was custom: “a head of lettuce has always exchanged for two eggs” or “a suit of clothes should cost about two silver shillings.” Money had been scarce since the barbarian invasions, and was just coming back into widespread use in Saint Thomas’ time, so barter was common.[2] The problem with custom setting the “just price” is, of course, that it utterly fails to take account of current conditions. Weather, war, pestilence, and blight can change the availability of goods very quickly. What no longer exists or is far more difficult to obtain simply cannot be traded at the low customary rate-What has become easier to obtain, perhaps through technology, will not be purchased at the high customary rate-new arrangements must be made, or there will be no trade at all. Saint Thomas would have seen the justice in this.

● In Saint Thomas’ time there were also prices fixed by “authority.” Towns sought to regulate the cost of goods and services. Guilds banded together to enforce the price they felt they deserved for their work. Kings, counts, and manor holders regulated products which they perceived to be essential to their realm. In modern times governments have felt called to set similar regulations, often with disastrous results-the disaster being proportional to the importance of the thing regulated, and the number of regulations put in place. (The best modern example is “rent control” whereby municipalities have made housing unavailable at any price by setting maximum apartment rental rates without regard to the housing market.)

While the lord of the manor may be in close enough contact to know what is available to and what is needed by the people on his estate, the King, whose territory is far flung, most certainly is not. But even when price regulations are made for apparently good reasons, they very often ignore the longer term consequences.[3] If the government dictates too high a price for something, few or none will buy it. If the government dictates too low a price for something, few or none will furnish it. The only way for the government to enforce an abnormally high or low price on something is by fine or imprisonment.. Even crazier things happen when the government tries to change prices by debasing the currency, something quite popular in our own time, again under the coercion under the guise of law.

A Spanish Scholastic, a successor of Saint Thomas, Juan de Mariana, S.J. (1536-1624), addressing both the regulation of price and debasement of the currency, wrote:

If money falls from the legal value, all goods increase unavoidably, in the same proportion as the money fell, and all the accounts break down....

Only a fool would try to separate these values in such a way that the legal price should differ from the natural. Foolish, nay, wicked the ruler who orders that a thing the common people value, let us say, at five should be sold for ten. Men are guided in this matter by common estimation founded on considerations of the quality of things, and of their abundance or scarcity. It would be vain for a Prince to seek to undermine these principles of commerce. 'Tis best to leave them intact instead of assailing them by force to the public detriment.[4]

● Father Mariana was clearly hinting at the only rational way in which fair prices can be determined: by bringing buyers and sellers together in an unrestricted market, allowing them to strike a bargain agreeable to both, and allowing them to denominate that bargain in money of constant value. The seller who demands too high a price will have no buyers, and will be replaced by competitors willing and able to sell at a lower price. The buyer who offers too little will find no sellers, or will offer more until one is found.

In a truly free market, in which many buyers and sellers participate, there are no monopolies or restraints of trade-prices held artificially high can only last until someone takes advantage of them to enter the market at a lower but adequate price. The monopolies and restraints on trade we see in modern economies are those conferred by government power on those who “work the system” to circumvent the free market.

The just price is the market price. Why? Because, as Saint Thomas would require, it serves the common good. When trade is conducted at the market price, no one is coerced, the maximum number of buyer’s and seller’s needs are met, and the means of production run at an optimal level. If the market price is tampered with by tax or subsidy, by wage or price controls, the balance is disturbed and goods go unsold, or goods are unavailable, or purchasing power is eroded by inflation.

A price above or below it is charity to the seller or to the buyer-charity is a good and commendable thing, but it differs from justice, which must always be observed; while charity is the occasional virtue, practiced on behalf of those unable to see to their own needs by those who have been able to earn surplus goods.

Mariana’s other point-“If money falls from the legal value, all goods increase unavoidably, in the same proportion as the money fell, and all the accounts break down”-is the other part of the “just price” question.

If a contract is negotiated at a particular price, the seller is defrauded if the value of the money goes down (more likely), and the buyer is defrauded if it goes up (less likely). Everybody holding money in reserve-buyers and sellers-is defrauded by the devaluation. The loss is the same whether the intent to debase the currency was based on a good or a bad reason-and debasement is so virtually unavoidable in modern money systems that it is hard to distinguish loss from fraud.

Coins can be devalued by filing off the edges (that is why someone invented ridges), or by minting them with less precious metal content. Few governments in monetary history have been able to resist the temptation-by taking gold or silver enough to mint ten coins and minting eleven, one can be put back into the treasury.

Paper money is far easier to debase. The underweight coins can be found by weighing them-but one paper note looks just like any other. And most money today isn’t even paper, but electrical impulses on a computerized ledger, spent into existence, and further multiplied by fractional reserve banking. Virtually every introductory economics textbook explains the method by which Central Banks create money-few such books explain the implication-that the more money created out of nothing, the less each monetary unit is worth.

● ● ●

So what is the relevance of all this to the question about the morality of gasoline prices?

Well, that price, like all other prices is a function of supply and demand, and the value of the currency in which it is purchased. What, then, are the factors of supply and demand, and what is the currency currently worth.

● Supply: OPEC is currently keeping oil output constant, refusing to pump additional supplies.

● Supply: US Domestic production 1955-1990 ranged from 200 million to 280 million barrels per month. Now at about 160 million.[5]

● Supply: US coastal and Alaska National Wildlife Refuge drilling is restricted or forbidden.[6]

● Supply: War and rumors of war, the build up of arms, and threats of war have destabilized the Middle East. On one day in early June, oil jumped by $11 a barrel when an irresponsible threat of attack was made against Iran.[7]

● Supply: Support of oppressive regimes in the middle east contributes to the danger of violence or revolution, with further disruption of oil supplies.

● Demand: Large underdeveloped economies like China and India have “come of age” and bring very large new demands to the market. US demand has dropped, but is no longer the controlling factor in the oil market.

● Demand: Alternative energy development hampered by socialist economics, ecological concerns, and peoples’ need to eat grains that could be turned into fuel.

● Taxes: About $60 billion annually (almost always higher than oil company profits). This does not include corporate taxes paid by oil companies, but are paid directly by consumers at the pump.[8]

● Taxes: Government officials threaten a “wind-fall profits tax on oil companies. Such a tax would produce no oil whatsoever, and would be an incentive to American companies to raise prices or move out of the market.

● Inflation: A policy of monetary debasement, paired with deficit spending, continually destroys the buying power of the dollar, while adding to the national debt which must be serviced with interest payments.

● Inflation: Monetary debasement finances wars without the warning sign of tax increases. We pay not only at the pump, but in the loss of human lives and limbs.

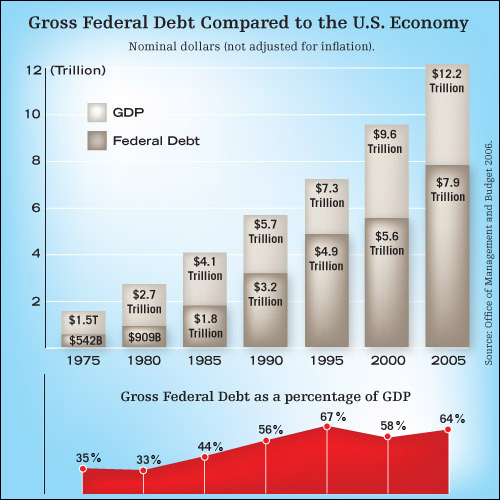

● Debt: The national debt is currently a bit over $9,400,000,000,000, growing about $1,580,000,000 each day. Your personal share of the debt is about $31,000 or $124,000 per family of four.[9] As a percentage of what the nation produces (GDP) the debt has increased from 35% in 1975 to 64% in 2005.[10]

Source http://media.npr.org/programs/morning/features/2006/mar/debtgraph3_500.jpg● ● ●

Are these moral issues? Setting the “just price” at the intersection of supply and demand is morally correct. The currency debasement certainly is not. Nor is war or posturing for war in all but the desperate need of self defense. Using less oil or developing greater reserves, or finding alternative energies might also have a moral dimension-these are things that need to be thought out with regard to long term consequences.

In our society, the solutions to these various problems can only come from the efforts of concerned and educated citizens making their demands known to their elected representatives. Those representatives must be required to act with economic prudence, seeking long term solutions rather than politically popular, counterproductive policies.

NOTES:

[1] ST. IIa IIæ Q.77. http://www.newadvent.org/summa/3077.htm

[2] Q&A April 2005 www.rosarychurch.net/answers/qa042005b.html

[3] MUST READING: Henry Hazlitt, Economics in One Lesson (New York: Three Rivers, 1979 edition.

[4] Jesus Huerta de Soto, Juan de Mariana: The Influence Of The Spanish Scholastics http://mises.org/about/3238

[5] http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/dnav/pet/hist/mcrfpus1m.htm

[6] http://www.anwr.org/backgrnd/potent.html

[7] www.nytimes.com/2008/06/07/business/07oil.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

[8] http://www.taxfoundation.org/news/show/1139.html

[9] http://www.brillig.com/debt_clock/

[10] http://media.npr.org/programs/morning/features/2006/mar/debtgraph3_500.jpg